Our book

To learn how the book came to pass, click here.

The land is our life in Kambi ya Simba. Soil, fields, pastures, streams, gardens, woodlands, these are the natural resources we hold close. In Tanzania, two-thirds of the population lives off the land. In our village, it is 100 percent. We are agro-pastoralists. Soil clings to our skin and covers our feet. We measure our wealth by the land we own. The national government gives every family in our village at least an acre. There we live with chickens poking about, perhaps a stand of maize, a compost pile, and a bucket of water. The prosperous among us own more land, a few as many as 30 acres. Their large fields meet the horizon. One acre or thirty, land is a fragile resource. Jacob Casmiri Dallan, who for 35 years oversaw land and agriculture in our village, tells some history. “It is like this. In the 1950s, the British government was keen on proper land planning. In villages like Kambi ya Simba, they proposed separating the land for grazing, cultivation, and forests. They recommended proper agricultural methods. With independence in 1961, these plans disappeared. Good or bad, they had no following. “So we proceeded without plans. We knew how to subsist, but not how to sustain. We grazed our cattle freely, harming our pastures. We plowed up hill and down, giving away our topsoil to the next heavy rain. We stripped forests for firewood, without replanting. And we grew. In 1960, our village had 700 people. Today there are almost 5,000. “Year after year, we took the fertility of our land for granted. We must now return to the soil the strength it once gave. For us, globalization starts under our feet.” Time has not, however, changed the spacious views across the Rift Valley to the east of our village or the huge shimmer from Lake Manyara. The soft panorama of mountains to the north and west makes us feel blessed.

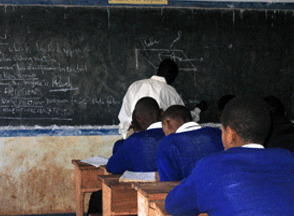

Writing down every word We are hungry for education here, as much as we can get. In our village, we have a nursery, two primary schools, and a secondary school. A half-hour’s walk separates each from the other. The secondary school is new, but thirty years of chalk-dust whiten the primary school blackboards. The primary school has over 850 students in eight grades, and 60 to 75 pupils to a class. Three hundred and fifty students attend secondary, which has four forms, and 40 to 50 pupils per class. We sit at wooden desks lined up in rows. The breeze blows through our classrooms. The walls are bare. We wear uniforms and when called on we always stand, prefacing our remarks with “Sir” and “Madam.” In secondary school, we take ten subjects, and speak only English. Our teachers are young and, we believe, wise. In Tanzania, only one in ten primary students achieve secondary school. Primary school is free, but secondary carries a tuition. In our village it costs 20,000 shillings ($20) a year, and parents must also donate, per term, 36 kilograms of maize and 13 kilograms of beans for day students, or 95 kilograms of maize and 34 kilograms of beans for hostel dwellers. We advance from form to form depending on how we score on national exams. If you are weak in a subject, help is scarce. One-quarter of our country’s population cannot read and write. Herieli Malle, the headmaster of Awet Secondary School, believes education holds the key to our village’s future:

To learn how the book came to pass, click here. |

PO Box 603252 • Providence, RI 02906 USA • Info@whatkidscando.org • 401.247.7665

Copyright © 2006, What Kids Can Do, Inc.

Soil covers our feet

Soil covers our feet